Following the earlier contributions to this blog series, which provided an overview of the six GNI-Internews fellows’ research projects, in this collection, fellows document their work over the last few months.

This post was originally published on Medium

Over the past decade, social media has become the most dominant source of information, a space for free expression, and a platform of opportunities for the Bangladeshi people. Facebook alone is now a 10 billion takas “F-commerce” market for at least 50,000 entrepreneurs; and there are several examples of criminals brought to justice as a result of social media outrage.

Social media in Bangladesh is almost synonymous with Facebook, with a share of more than 95% of the market. It is a platform of choice not only to share information, but also to express dissent and publish critical content, as the democratic space in Bangladesh is shrinking.

According to Freedom House, the ruling party “has consolidated political power through sustained harassment of the opposition and those perceived to be allied with it, as well as of critical media and voices in civil society.” The mainstream media continues to self-censor for fear of imprisonment or closure; and there are three detentions in a day under the controversial Digital Security Act (DSA), which makes “negative propaganda” punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

Under such a political environment, the need for protecting speech on social platforms has become more significant than ever. But this space has rather turned into a graveyard for the most critical voices. There is more control and surveillance over platforms, and journalists and activists are being charged and arrested for critical online expressions, under the DSA. On another front, their social media accounts are being taken down, which they believe is a result of false reporting by bad actors — political, state-sponsored, and religious — finds my research under the GNI-Internews fellowship.

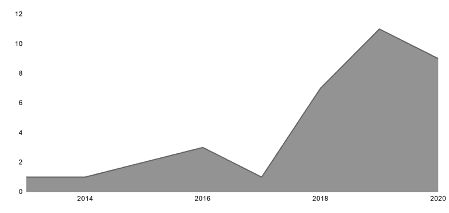

The research identified 40 Bangladeshi journalists, bloggers, and activists who are reported to get their Facebook accounts disabled, and interviewed 17 of them for a survey, who went through such experience in the last four years. Results suggest that this trend has grown significantly from 2018, the year of national election. 56% said it happened with them more than once, and for some, even 5–6 times. They also find Facebook at fault for not doing enough to protect the sensitive speech on their platform.

Facebook says it disables an account if a user does not follow their terms. But respondents said that they did not violate any, disagreeing with its decision. However, 53% of the respondents could not get their account back and eventually had to open a new one.

Eight among the interviewed said that they have been reported by trolls for having a fake profile. In these circumstances, Facebook requires the owner to pass a series of steps to prove that the account is authentic. But one journalist, who is also a caustic critic of the government, found that someone opened a fake profile in his name and provided “attested” identification documents to Facebook pretending to be him. Facebook finally judged the real account as fake, and he could not get it back even after submitting original proofs.

In another case, a blogger found his account was “memorialized” as someone reported him to Facebook as dead and provided them “official” proof of his death. In both instances, bad actors manipulated Facebook’s account recovery process to silence critics. Another journalist said that he had to prove his identity at least ten times before getting it restored.

A woman journalist, on the other hand, posted about a six-year-old girl wearing veils. And since then, radical religious groups accused her of being “anti-Islam,” opened a fake account in her name, and started mass reporting against the real profile to get it disabled by Facebook permanently. Even after filling in forms several times, she could not get it back.

When asked how they rate Facebook’s account recovery process on a scale of 1–5, where one is “very good,” and five is “very bad” half of the respondents rated it as very bad, and only 18% as “good.”

Major concerns identified by interviewees are that Facebook’s content moderators do not understand the country context, that people who experience account deactivation never have the opportunity to talk to anyone at the company, and that sometimes it is hard to explain things in emails in a foreign language (English) to a foreign individual. “Even if I write about injustice, they ban that based on false reports,” said an activist.

One of the strategies Facebook has used to raise awareness of its Community Standards has been to make them available in many languages, including Bangla. However, the survey finds 70% of the respondents were not aware of the fact that a version of the Community Standards exists in Bangla; and 65% found the quality of translation either bad or very bad when asked to read the first two paragraphs.

Facebook’s decision on what action to take on an account largely depends on technology. “Our software is built with machine learning to recognize patterns, based on the violation type and local language,” said the company in a guide to understand the Community Standards enforcement report.

It also says that their software hasn’t been sufficiently trained to automatically detect violations at scale; and reports from the community help them to identify new and emerging concerns quickly, as well as to improve the signals. Survey respondents widely believe that vested groups are these features against journalists and activists.

Nathalie Maréchal, Senior Policy Analyst at Ranking Digital Rights (RDR), also believes it is possible. “When a group of people decides to mass report people because they simply disagree with their point of view, identity, or something else, I think that has a very real potential to skew the machine learning systems,” she said in an interview.

Facebook’s latest Civil Rights Audit also mentioned that it is essential for the platform to develop ways to evaluate whether the AI models it uses are accurate across different groups and whether they needlessly assign disproportionately negative outcomes to certain groups.

Apart from the survey respondents, this research interviewed civil society leaders and experts, including Raman Jit Sing Chima of Access Now, Thenmozhi Soundararajan of Equality Labs, RDR’s Nathalie Maréchal, Victoire Rio of Myanmar Tech Accountability Network, and Grant Baker of SMEX for recommendations. Here is what they suggested:

- Inform the account owner before disabling it. Let them respond to the complaint first, review that, and then decide. And how decisions are taken against a reported profile should be made transparent.

- Educate users.The media and activists need to understand, in practice, what the Facebook system considers as acceptable and what is not, and how to avoid mistakes.

- Digital security helplines — as currently operated by Access Now and several other organizations, and which can help take the critical cases to Facebook — is a short-term solution, though not scalable.

- Collaborate with local civil society to include critical actors in Facebook’s “Crosscheck” program that systematically make sure there is a human review before any sanction decision on them.

- Increase staff at the regional level for content moderation and to handle specified requests who speak the local language and have the appropriate cultural context. And develop mechanisms to check internal biases of local staffs.

- Ensure regular third-party audit of training datasets of AI to assess how the system works and where they are failing; as content moderators may install a systemic bias into the system, if their review is biased. Automated moderation needs more transparency.

- Facebook is not transparent around government and political actors in South Asia. Government-sponsored or political actor-driven attempts to censor people, need to be noticed. Their content operations and content governance team in the Asia Pacific require more engagement with civil society.

- Facebook’s business model creates incentives that are contrary to human rights and to the user’s needs. In the long-term Facebook needs to change completely and the best way to achieve that is through legislative and regulatory changes in the US.